So you want to get into photography and are looking for a decent camera that you can build a system around?

A few years ago that was easy question to answer – you had to buy a DSLR if you wanted to get creative with your photography. But then in 2008 Panasonic launched the world’s first mirrorless camera, the Lumix G1, and everything changed.

Like DSLRs, mirrorless cameras (also known as CSCs or compact system cameras) allow you to change lenses, but as the name might suggest, they don’t feature a complex internal mirror system like DSLRs do.

This means that they can in principle be smaller, lighter and mechanically simpler than an equivalent DSLR. It also means that they can also be just like super-sized compact cameras to use, whereas most DSLRs are a bit of a jump from a regular compact camera.

Enthusiasts and pros, however, have taken a bit of convincing on the merits of mirrorless cameras. The absence of an optical viewfinder, streamlined controls and limited lens range for most systems was a turn-off for a lot of experienced photographers.

That’s all changing though. As manufacturers widen the lens range and options available, lens choice is becoming less of an issue, while a raft of new mirrorless cameras have arrived to tempt photographers away from the more traditional DSLR, with performance and image quality in some instances bettering DSLR rivals for a similar price.

The question is then, have mirrorless cameras done enough to be genuine DSLR rivals or, more to the point, are they already better? To help you decide, here are the key differences and what they mean for everyday photography.

- Size and weight

DSLR: Can be big and bulky, though this can be a help when shooting with big telephoto lenses (and big hands)

CSC: Yes, they are generally smaller and lighter, but the lenses in some cases can be just as big as a DSLR’s

Compact proportions is one of the big selling points for mirrorless cameras, but it doesn’t always work out that way because what you actually have to take into account is the size of the camera body and lens combination.

This is a problem for mirrorless cameras with either full-frame or APS-C sized sensors because you can get a nice slim body but a fat, heavy lens on the front. Some models now come with retractable or power-zoom ‘kit’ lenses, but that doesn’t help when you have to swap to a different type of lens.

Panasonic and Olympus cameras have an advantage here. The Micro Four Thirds sensor format is smaller (which many photographers don’t like) but this means the lenses are smaller and lighter too (which many do), delivering a much more compact system all round.

Interestingly, some higher-end mirrorless cameras like the Sony Alpha A9, Panasonic Lumix G9 and Canon EOS R, are now growing in size as they take on more features and manufacturers respond to feedback from photographers who want larger grips.

At the end of the scale, entry-level DSLRs are shrinking to compete with the smaller footprint of similarly priced mirrorless cameras.

2. Lenses

DSLR: Both Canon and Nikon have a massive lens range for every job

CSC: Olympus, Panasonic, Fujifilm and Sony all have a solid, but not quite as comprehensive lens ranges

If you want the widest possible choice of lenses, then a Canon or Nikon DSLR is possibly the best bet thanks to their huge range of optics – they both have an extensive range of lenses to suit a range of price points, as well as excellent third party support from the likes of Sigma and Tamron.

While Canon and Nikon have both had decades to build-up and refine their lens line-up (Nikon’s lens mount is unchanged from 1959), the first mirrorless camera only appeared 10 years ago. However, mirrorless cameras are certainly gaining ground. Because Olympus and Panasonic use the same Micro Four Thirds lens mount and have been established the longest, the range of Micro Four Third lenses is the most comprehensive, offering a broad range of optics, from ultra wide-angle zooms to fast prime telephoto lenses.

Fujifilm’s lens system is growing all the time, with some lovely prime lenses and excellent fast zoom lenses. Even the 18-55mm ‘kit’ lens is very good. There’s still a few gaps in the range, but Fujifilm’s definitely working hard to deliver a comprehensive and high-quality range of lenses.

Sony offers some really nice high-end optics that are designed for its full-frame line of cameras like the Alpha A7 III, while its just launched a mighty 400mm f/2.8 telephoto prime lens.

Both Canon and Nikon have recently launched full-frame mirrorless cameras to run alongside each company’s DSLR range. At the moment, the dedicated optics for each are limited to around three lenses, but both Canon and Nikon offers affordable adapters that will allow you to use lenses designed for DSLRs (though only the newer lenses offer full compatibility).

3. Viewfinders

DSLR: Many photographers still prefer an ‘optical’ view for its clarity, natural look and lag-free viewing

CSC: Others though prefer to see a digital rendition of the scene as the camera will capture it

All DSLRs, even the cheapest, come with an optical viewfinder because it’s an integral part of the DSLR design. However, quite a few entry-level mirrorless cameras don’t have viewfinders at all, so you have to use the rear LCD to compose photos, which doesn’t always work so well in bright light.

Mirrorless cameras with viewfinders cost more, and these are electronic rather than optical viewfinders – they display the image direct from the sensor readout and not via an optical mirror/pentaprism system.

Electronic viewfinders are advancing in leaps and bounds, so the latest rarely show any pixelation or ‘granularity’ that was an issue in earlier generations, though there can often be a slight but visible ‘lag’ if you move the camera really quickly.

The advantage of electronic viewfinders is that they can display a lot more information than an optical viewfinder can, including live image histograms, for example. They can also simulate the digital image the camera will capture, so you don’t get any horrible surprises when you review your image as it’s exactly what you’re seeing.

This simulation is not always perfect, however, and many photographers prefer to see the world with their own eyes as they compose the image and check the digital version on the LCD straight after it’s been captured. They’re also easier to use in low-light.

This will come down to personal preference – get one of the latest high-end mirrorless cameras with a large magnification, large resolution electronic viewfinder, and you’ll be hard pressed to find fault with it.

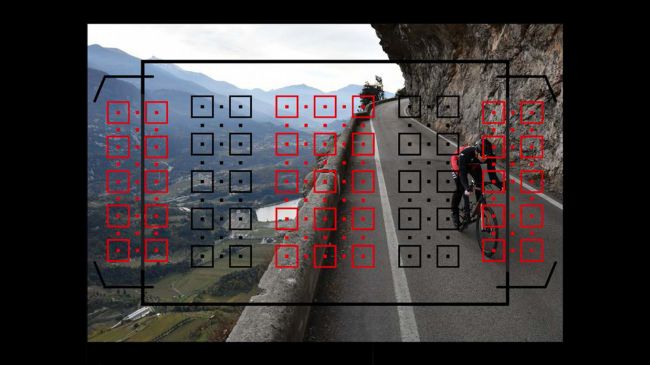

4. Autofocus

DSLR: Used to have a clear advantage, but not quite as clear-cut now. On the whole they’re better for tracking fast subjects, but can be weak in Live View

CSC: Live View AF performance is generally very good when using the LCD screen, while latest models can have excellent overall AF performance when using the EVF

DSLRs use fast and efficient ‘phase detection’ autofocus modules mounted below the mirror in the body. This system can be incredibly fast at focusing and tracking subjects, with camera’s like the Nikon D850 featuring incredibly sophisticated system.

The trouble is that these systems only work while the mirror is down. If you’re using a DSLR in live view mode, composing a picture or video on the LCD display, the mirror has to be flipped up and the regular AF module is no longer in the light path. Instead, DSLRs have to switch to a slower contrast AF system using the image being captured by the sensor.

The latest Canon DSLRs (such as the EOS Rebel T7i / EOS 800D, EOS 80D and EOS 5D Mark IV) though include the company’s brilliant Dual Pixel CMOS AF that uses phase-detection pixels built into the sensor. This is designed to give faster autofocus in live view mode to close the gap on mirrorless cameras and it works very well indeed.

Mirrorless cameras have to use sensor-based autofocus all the time. Most are contrast AF based, but these tend to be much faster than equivalent contrast AF modes on DSLRs, partly due to the fact the lenses have been designed around this system.

More advanced mirrorless cameras have advanced ‘hybrid’ AF systems combining contrast autofocus with phase-detection pixels on the sensor, with the likes of the Fujifilm X-T3, Panasonic Lumix G9 and Sony Alpha A9 really impressing with not only their speed, but with the accuracy at which they can lock on and follow a moving subject – the one area where DSLRs have, until now, had a clear advantage.

5. Continuous shooting

DSLR: The best DSLRs can no longer match the speeds of the best CSCs

CSC: The mirrorless design makes it easier to add high-speed shooting

You need a fast continuous shooting mode to capture action shots, and mirrorless cameras are streaking ahead here, partly because the mirrorless system means there are fewer moving parts and partly because many models are now pushing ahead into 4K video – this demands serious processing power, which helps with continuous shooting too.

To put this in perspective, Canon’s top professional DSLR, the EOS-1D X Mark II, can shoot at 14 frames per second, but the mirrorless Panasonic Lumix G9 and Sony Alpha A9 can both shoot at a staggering 20fps.

You have to be a little careful though when looking at the spec. Some mirrorless cameras will boast even higher frame rates than this (in some cases, up to 60fps), but will have to use an electronic shutter to achieve this and focus will be fixed from the first shot. Not great if you’re planning on tracking a moving subject.

You’ve also got to be realistic about what kind of burst shooting speeds you are going to need – shooting at 60fps means you’ll fill up a card pretty quickly, while you’ll have to spend a lot of time trudging through a multitude of images to find that ‘one’ shot. That said, with even entry-level mirrorless cameras offering faster burst shooting speeds than most DSLRs, mirrorless cameras certainly have the edge if this is your main concern.